Coming down from the stage

Hi friends,

First up, a reminder that I’ll be in Queens for a conversation with Brooke Shaffner and Jess DeCourcy Hinds on Friday, May 3, 7:00 p.m., at Kew & Willow Books. We’ll be chatting about gender and street art in literature plus a lot more, and I hope you’ll join us!

It’s been a long time since I’ve been to a live music show in a small venue. A friend of my husband’s alerted him to a band who was coming through town called Dirt Wire, and neither of us had heard of them, but their blend of country twang, instrument experimentation, and electronica was intriguing enough to make us buy tickets. So last night we packed ourselves into a dark bar and experienced one of the most interesting live performances I’ve seen in a while.

During their last song of the show, the band also did something that delighted me. One of them announced, “We’re gonna come join you in the audience with our drum kit,” and then they lifted their drums in the air, walked down from the stage, and parked their instruments and themselves right in the middle of the audience, who made a tight circle around them and, cheering, held up their phones.

The band taught everyone a quick melody and cued us to chant it on repeat, surrounding themselves with our voices as they played. And some members of the audience got up on the stage to get a better view of them. As I watched Dirt Wire get subsumed by bodies and voices, soon I could no longer see them, and it occurred to me that with these two small moves, they’d completely changed their relationship with the audience—and therefore the whole experience of their music.

This morning, I woke up thinking about writing, as I too often do, and I started to consider what it means for a writer to take a surprise turn like that, that changes their relationship with the reader. The first examples that came to mind were stories that use the second person (you) or first-person plural (we), implicating the reader in the narrative. But if an entire story is written from one of those POVs, then that in itself doesn’t really count as a surprise or change in the relationship.

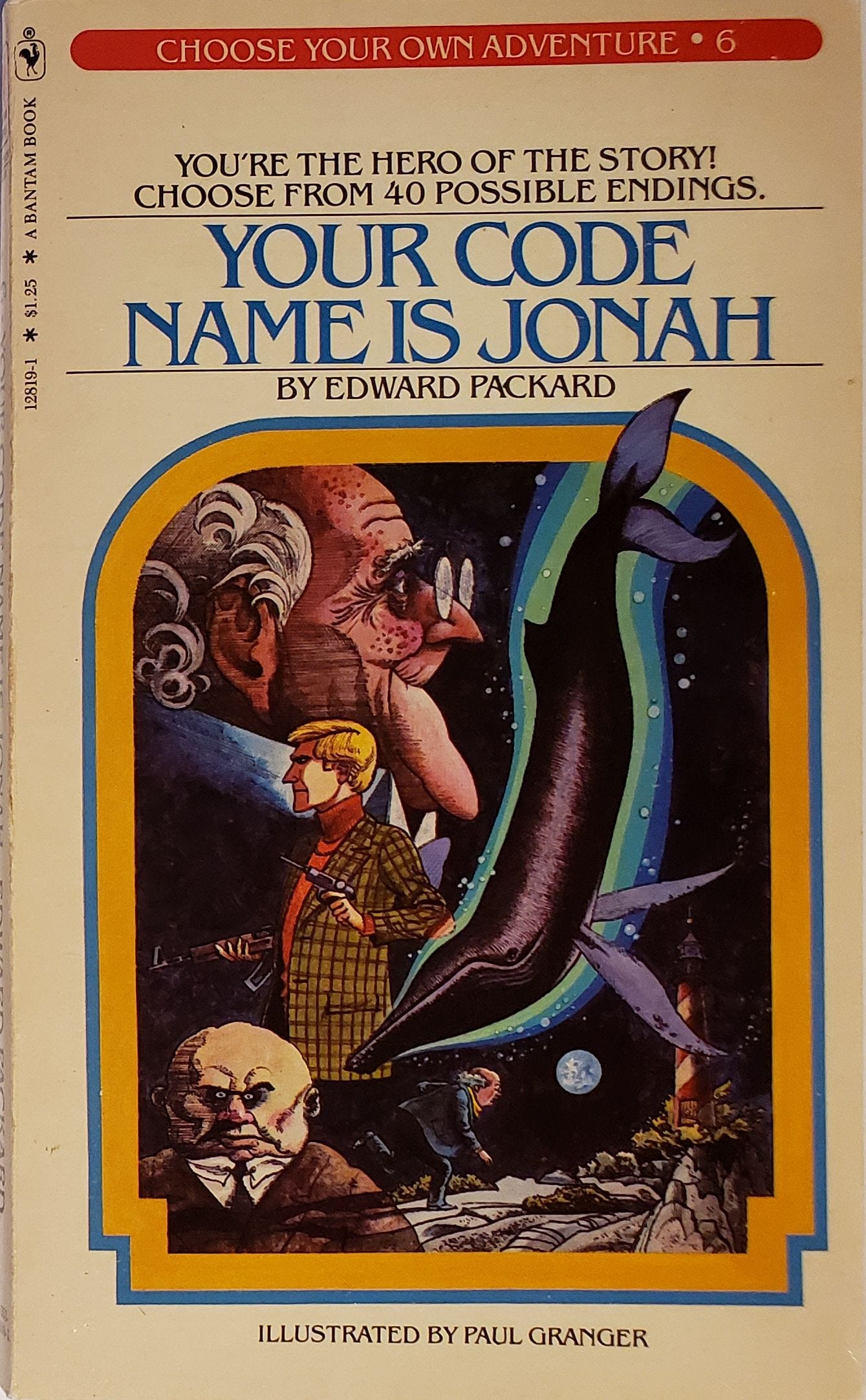

So then I got to considering novels that make these kinds of turns unexpectedly. And of course, as a child of the ’80s, the first thing I thought of was the Choose Your Own Adventure series, and then my husband reminded me of Griffin & Sabine, the famous 1991 epistolary novel that included letters and postcards in envelopes that the reader could pull out and read.

Because I primarily write literary novels, however, I also wanted to think about how literary novelists can or do deploy similar tactics to interesting effect, and a few came soaring to mind: If On a Winter’s Night a Traveler by Italo Calvino, The Emigrants by W. G. Sebald, Memorial by Bryan Washington (yes, I talk about this one a lot!), and I Keep My Exoskeletons to Myself by Mac Crane.

In Calvino’s beloved novel, reader expectations are played with from the first sentence, but Calvino doesn’t stop there. To quote David Mitchell in The Guardian:

"You are about to begin reading Italo Calvino's new novel, If on a winter's night a traveller. Relax. Let the world around you fade." From the opening line of this eccentric book, which I first encountered as an undergraduate 16 years ago, I was magnetised. It was everything that A-level A Passage to India and As You Like It hadn't been. A novel that referred to its own existence? As offworldly an idea as the non-existence of the Soviet Union. A second-person protagonist? Unthinkable as two George Bushes.

Then there was the novel's giddying (what I soon learned to call) intertextuality, where the protagonist "You" comes across 12 manuscripts written in the style of a Bogart movie, Borges, Chekhov, a spaghetti western, Mishima, and so on. And how about the audacious structure? Each manuscript is interrupted after too few exquisite pages, obliging "You" to hunt for its continuation through a landscape of bookshops, rarefied campuses, shifty publishers, refined censors, reading rooms and literary guerrillas.

Each time "You" (and you) get your hands on the continuation of the last interrupted story, it turns out, agonisingly, to be a brand-new one: but each one, after a line or two, becomes as enticing and addictive as its predecessor…

In The Emigrants, Sebald uses an interesting blend of fiction and memoir, including photographs that sometimes obscure more than they reveal, keeping the reader in a sort of heightened state of activation, inviting them to bring their own beliefs and interpretations to bear on the novel.

From André Aciman in The New Yorker:

As a writer, Sebald had invented an arcane aesthetic by cobbling together things imagined and things recalled; his essays and novels challenge the idea that facts hold a greater claim to truth than misremembered faces, overlooked details or overheard gossip. Aunt Egelhofer, who was real, was Sebald’s gateway to the world of the Wallersteins, who were also real. And yet their narrative hovers in a misty zone typical of Sebald, who was loyal to neither history nor fiction but rather to an unstable confluence of invention, memory, and imagination.

Photographs also play a key role in all of Sebald’s books, casting an aura of documentation and verisimilitude on the narrative, and yet they are also vague and unreliable. Blurry images and illegible handwritten notebooks emphasize the imminent extinction of objects, people, places, or buildings that are already, or perhaps always were, on their way out…. As a narrator in “The Emigrants” writes, “I leafed through the album that afternoon, and since then I have returned to it time and again, because looking at the pictures in it, it truly seemed to me, and still does, as if the dead were coming back, or as if we were on the point of joining them.”

In Washington’s Memorial, the change in the author or narrator relationship to the reader occurs about halfway through, when the first-person narration shifts from Benson, who’s POV we’ve been in from page one, to his boyfriend, Mike. After 132 pages of Benson’s voice, internal life, and struggles, just when readers are 100 percent invested in his side of things, Washington takes this surprising turn, throwing us not just into another POV but into a different country. Mike has left Benson in Houston with Mike’s mother, Mitsuko, to visit his dying father in Japan, but how long he’ll be gone is uncertain. When we change to Mike’s POV, therefore, we change not only point of view and country but story. We’re in thrust into Mike’s world, which, at least for now, doesn’t even include Benson or Mitsuko.

At first, I found this move to be jarring at best and disconcerting at worst. I wanted Benson back; his story wasn’t finished. But it didn’t take long before I was equally invested in Mike’s POV and how it related to Benson’s and everything it revealed about their relationship. Later, for the last quarter or so of the novel, we’re returned to Benson’s POV.

In Memorial, Washington takes a big risk, but for this reader, the abrupt change in the narrator/reader relationship pays off big time.

Finally, in I Keep My Exoskeletons to Myself, a speculative novel about grief and loss in a world where criminals are given extra shadows and surveillance is constant and everpresent, Crane employs an experimental style, narrating the book in fragments that resist a linear flow and pop quizzes that suddenly and momentarily place you, the reader, at the center of the story, implicating you in the protagonist’s feelings and experiences.

A few examples:

Pop Quiz:

Q: What will you fill yourself with today?

A: Imagine this is a five-paragraph essay response, with an oddly touching conclusion.

Pop Quiz:

Fill in the blanks:

Many people in the United States find it _____ to _____ about _____ until it _____ to them.

And then there’s at least one pop quiz that’s a word find, and none of the words can actually be found in the grid of letters that follows.

As I revise my novel-in-progress this week, the idea of changing the author-or-narrator/reader relationship feels like a fruitful place to allow my imagination to dwell. Whether it’s a small shift at the sentence level or a big turn in the book as a whole, if it’s done in a way that supports the work—and not as a gimmick for the sake of itself—changing this relationship can have profound effects on the reading experience.

So as I work this week, I’m going to imagine what it means to come down from the stage and engage with my readers in a different way, and I hope you find something useful in imagining this too. Meanwhile, I hope you have a great week, and hope to see you in Queens on May 3!

Yours,

Jen

Great essay. Thanks!

As a writer, you should get off the stage and sit in the reader's lap : )